There is a growing respect for the history of Aotearoa New Zealand with the uptake of a new history teaching curriculum and initiatives like Te Pūtake o te Riri (New Zealand War Commemorations).

With the growing attention on the relatively short history of settlement in the country, you may be thinking that we know all there is to know about the past and now it’s just a case of learning it.

Oh no, my friend! With each passing year, new understandings are brushed off and debated, enabling fresh insights into who we are and how our society formed in the way it did.

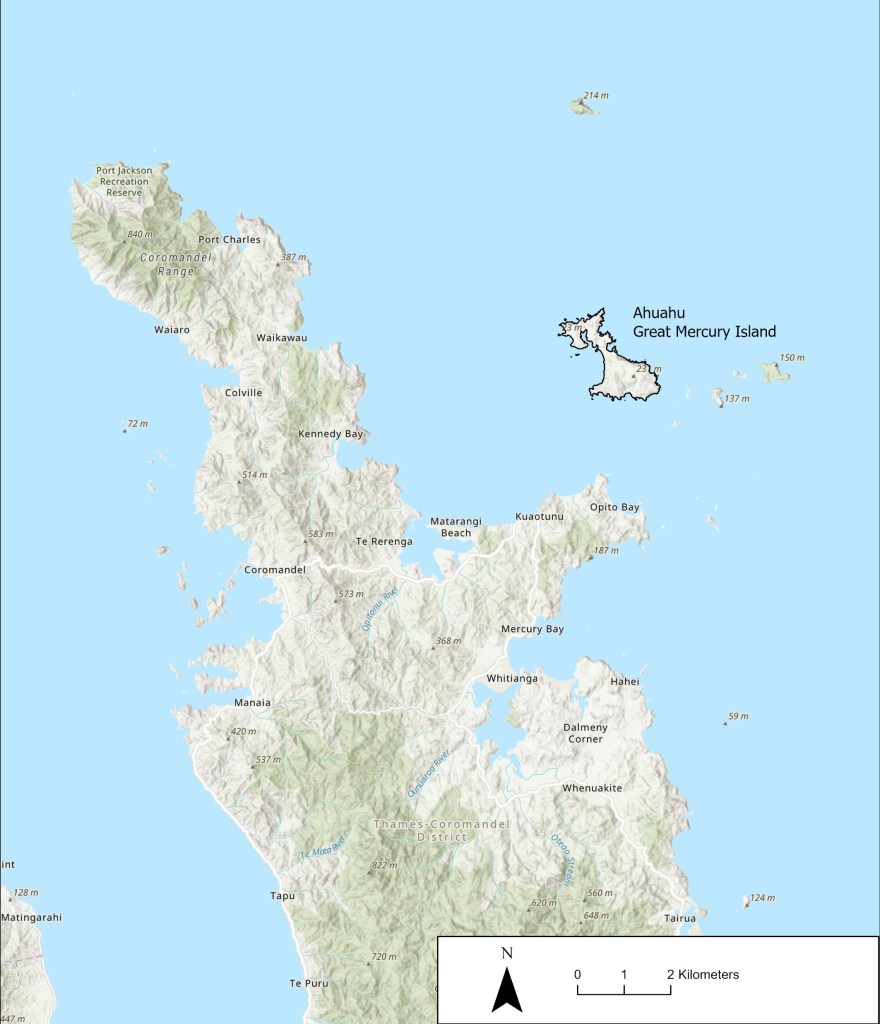

One significant place where our knowledge of the past has grown significantly over the past decade or so is Ahuahu (Great Mercury Island), located offshore of the Kuaotunu Peninsula on the east coast of the Coromandel Peninsula.

Fortunately for you, dear reader, just a few months ago, an archaeological expedition went out to the island joined by Ngāti Hei to hīkoi (tour) around significant sites. So, what goes on at Ahuahu, what was uncovered in November 2023, and why should you care? Find out below and read the words of one Ngāti Hei uri (descendant) who joined the hīkoi.

There was a sense of awe, in seeing the terraces of headland pā, and thinking of all the work in creating those kainga, still visible after so many centuries.

Tiki Johnston (Ngāti Hei)

The archaeology project

Several kōrero tuku iho (inter-generationally transmitted oral histories) describing the Polynesian migration events from Hawaiki (the ancestral homeland) to Aotearoa refer to Ahuahu as a critical place associated with early settlement on the eastern coastline of Te Ika-a-Māui (North Island).

Today, many hapū regard Ahuahu as a significant place in their histories — as whenua tūpuna (ancestral land) providing a link between kanohi ora (living people) and ngā mātua tūpuna (ancestors). The iwi (tribe), Ngāti Hei, has a deep and persistent historical connection to Ahuahu and partners with current island owners, the Fay and Richwhite families, and the University of Auckland’s Archaeology Department to learn more about the island’s history.

The current bout of archaeological research on Ahuahu (earlier work having been undertaken by Jack Golson in 1954, Steve Edson in 1972–1973 and Geoffrey Irwin in 1984) began in 2012. On a personal note, this was also the year that I first put trowel to land in the archaeological field school, galvanising my passion for archaeology.

In November 2023, Professor Thegn Ladefoged led an excursion of researchers from the University of Auckland and the University of Otago back to Ahuahu to further investigate an area known as “Takapau” and “Waitetoke”, located on the tombolo between two larger bodies of land on the island to the north and south.

This phase of research was part of a Marsden-funded project led by Te Pūnaha Matatini (a Centre of Research Excellence studying complex systems) with the aim of understanding the complex ways in which Māori in Te Ao Tawhito (before European contact in the late seventeenth century) interacted and formed their environments and ultimately became changed by those environments. No small task!

Takapau and Waitetoke

Previous work had recorded a series of stone-faced terraces, stone alignments and evidence of buried cultivated soils. These were all that remained of generations of industry by tangata whenua who had first settled the area, cleared the forest, planted introduced food crops, and tended their cultivations — i.e., making a home.

Led by Dr. Matiu Prebble, detailed inspections of microscopic plant and insect remains preserved in soils had already revealed that tangata whenua had actively cultivated taro and kūmara — crops that had been introduced to Aotearoa from Hawaiki by Polynesian voyagers — at that very spot.

The evidence suggests that after the rimu dense island forests were cleared from the area, the tropical crop, taro, was cultivated between 1425 and 1600 CE. After this time, people favoured kūmara, probably because it is more hardy and produces more food than taro in northern temperate Te Ika-a-Māui.

All this information about the old people came from a few sampled bags and cores of dirt! Amazing!

November 2023 Fieldwork

During the waxing moons of Whiringa-ā-rangi (October-November) of the maramataka Māori (lunar calendar) and under the mana of Ngāti Hei, the archaeology team set to work to further explore the limits of the former cultivations that had been planted over several seasons perhaps under the same Whiringa-ā-rangi lunar phase, several hundred years before.

We laid several excavation trenches that had not been completed in earlier excavation seasons. Wait, wait…That’s a funny thought — What does it take to finish a trench???

Well, archaeological excavations are destructive, an idea that is at the forefront of a good archaeologist’s mind when planning any excavation. If we are to disturb wāhi tūpuna (ancestral places), we need to ensure that we record what is uncovered in detail to preserve that information.

The trade-off in recording in great detail is that hand excavation can be slow (think hearth brushes and hand trowels!). Without such care and patience, important clues can be lost in the spoil piles of an overly excited digger. When time is up, and a trench has not been excavated fully through the “cultural layers” of sediment deposited or made by human activity, archaeologists cover unfinished trenches with a cloth or tarpaulin that can be easily relocated.

What did we find?

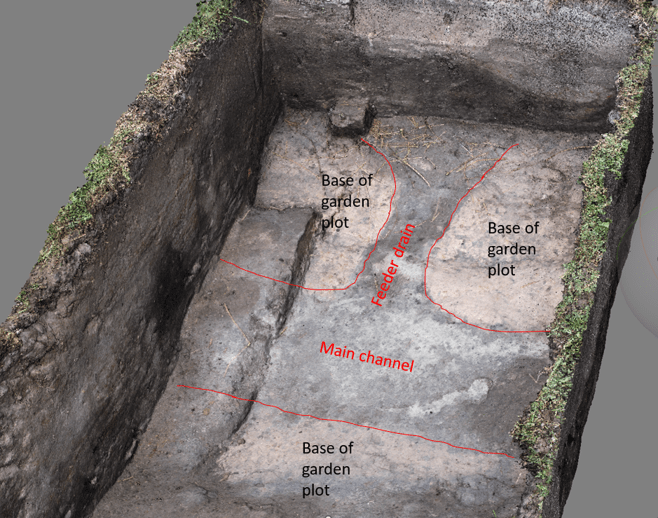

Once excavations were in earnest, the team excavated and recorded remains of kūmara and taro cultivation beds, irrigation trenches, fire features, post holes and stone artefacts. Despite what I have said before about midden, we recovered very few food remains in the form of bone and shell. Today, let’s focus on the evidence of māra kai (food cultivation).

Maybe you have done some planting in your mum’s yard or out back of the marae, but what would your great, great, great, great, great grandparent’s cultivation beds look like today?

Past māra kai can be identified by looking for stone alignments on the surface, where gardeners had clear surface stones and stacked or aligned them in certain ways to possibly reflect whānau plots, limit surface erosion of precious soils or increase local soil fertility through leaching. Stone alignments are clearly visible at Takapau — so much so that the place name uses the imagery of a chiefly woven mat to describe the criss-cross pattern of stone walls here (refer to aerial image earlier in this post).

Māra kai remains can also be detected by excavating a trench into the ground and checking out the exposed vertical profile of sediment. At Takapau, we observed the tell-tale signs of cultivated soils with charcoal chunks from tilling burnt-off vegetation after initial forest clearance or periods of fallow (when lands were let rest for a period to naturally restore soil fertility). We also saw streaks of underlying sediment within the soil layers themselves, where gardeners had tilled through the soil layer.

Not only did we detect this streaking pattern, but we also detected the marks of that tilling action below the garden soil, where kō (cultivation implement) had scraped against the underlying sediment. These are some of the special occasions as an archaeologist where you can see the remains of a single person’s action — digging in the māra kai. I have worked as an archaeologist for over a decade, and these connections with those gone before still strike me and make my hair stand on end.

Another cool aspect of the excavation was uncovering the remains of irrigation ditches! So, not only were tangata whenua actively clearing, planting cultivating at Takapau and Waitetoke, in early stages they also actively managed the flow of water from a puna (spring) to irrigate taro crops.

These irrigation channels were not visible on the surface and were not known to have been there today. However, through careful archaeological research on Ahuahu, work over recent years and continued this year have uncovered and carefully documented these channels to explore their capacity, function and alignments to build a comprehensive understanding of their importance in relation to the taro cultivation here.

Archaeological evidence of irrigation is not too common in Aotearoa and is much more widely practiced in the tropical Pacific, like the great pond fields of windward Hawai’i. Each instance demonstrates localised innovations and dynamic environmental relationships by the tāngata whenua and kānaka moali.

Why is this work important?

I offer you two reasons:

- The results of this ongoing research project contribute significantly to our understanding of tangata whenua histories of settlement in Ahuahu and Aotearoa. This localised study of māra kai provides information on plant introductions, climate adaptations and innovations that remain relevant to our changing world today.

- The archaeological research is an opportunity for Ngāti Hei and other interested iwi to learn more about the achievements and lives of their ancestors. Kōrero tuku iho tells us so much about the past, but archaeology can provide glimpses of the lives of those perhaps not recorded in the histories while providing overarching narratives of change through time over hundreds of years. Both forms of knowledge have a place in understanding the past.

The significance of Ahuahu and the findings of the archaeological research progress was clear when Ngāti Hei joined members of the research team in discussing trenches exposing the remains of māra kai and going on an island-wide hīkoi (excursion) to places of significance.

Mātauranga and archaeological information was offered and discussed. But beyond the knowledge, were new senses of connection amongst ngā hunga ora (living people) and with ngā hunga mate (those passed) made possible through engaging with place, archaeological practice, kaitiakitanga (stewardship) and whanaungatanga (relationship building).

Tiki Johnston (Ngāti Hei) offers her perspective of the trip in her own words:

It was a privilege for us as Ngāti Hei iwi members to spend time with the Ahuahu Archaeology Project kaimahi out on Ahuahu. Thanks for all the planning, and for the boat trip – which was also a great chance for whakawhanaungatanga and sharing of kōrero, as we passed through our rohe moana, and looked out at motu we have heard much about – Ohinau, Whakau, Ahuahu. Thanks also for the delicious lunch!

It was a wonderful experience for our whānau to share kōrero and mātauranga, on Ahuahu – which we have heard spoken of as “our Hawaiki” – as the place our tīpuna came to, and then from. I’d heard stories of this place of bounty, where kūmara were so plentiful they could tumble from the cliff into the waka, this kōrero came alive as we moved through the landscape.

The painstaking work of the archaeologists was explained patiently and clearly. Through this mahi we had a glimpse into the lives of our tīpuna – their hard work, their ingenuity, their adaptability – changing the landscape, using rock, water, and fire to create cultivations of taro and kumara from such early times. It was a profound experience to see the great, white rhyolite cliffs – Pari-nui-te-rā — which we have heard were the signal for waka in ancient times that they had reached their destination. There was a sense of awe in seeing the terraces of headland pā and thinking of all the work in creating those kainga, still visible after so many centuries. We could see the landscape is so rich in history, and learning about your work gave us a window into the lives of our earliest tīpuna. While for me, it was my first time on Ahuahu, it also felt like a homecoming — to our ūkaipō. Nā reira, e ngā ahorangi, e rere kau ana ngā mihi hōhonu ki a koutou.

Thank you for reading this blog post. As always, share this page with a friend and be sure to subscribe, so you don’t miss the future fuss. Ka nui te mihi atu ki a Tiki rātou ko Ngāti Hei whānui anō. He mihi hoki ki ngā iwi maha e hono ana ki Ahuahu. Whēoi anō me ngā mihi nui atu o te tau hou Pākehā ki a koe, ki a koutou katoa, nā Zac.

One thought on “What was recently uncovered on Ahuahu Great Mercury Island?”