Archaeologists have several techniques to help identify potential buried archaeological evidence that is not visible on the surface:

- Desktop research (including historical information, legacy data, aerial and satellite imagery, LiDAR)

- Field survey (including visual inspection, geophysical techniques, test excavations)

- Predictive modelling

Nau mai hoki mai! Welcome back, curious minds!

Looking at this title, I know you are thinking, Zac, you have just been going on about how archaeology isn’t all about digging!

Yes, you are right. However, excavation is essential to an archaeologist’s toolkit to learn more about our unique cultural heritage or recover archaeological remains from ancestral places before they are destroyed by development or erosion.

Often archaeological evidence is completely buried, or only certain parts of buried features and structures may be visible on the ground. Yet, archaeologists keep generating new knowledge and uncover many exciting things.

So, how do archaeologists know where to look? Let us spill the dirt on this oft’ asked pātai.

Desktop research: know before you go

Archaeologists do not possess X-ray vision (well, I don’t), so we have to gather as much information and tools as possible to make educated guesses where archaeological evidence is likely to be buried.

Kōrero

People with longstanding connections to cultural heritage places and surrounding lands usually hold information about where archaeological evidence is likely to be.

These people could be descendant’s of the people who made the archaeological evidence that you are interested in or the local land owner who inherited the land from her mother.

Humility is an essential part of a good archaeologist’s toolkit. By simply asking people about whether they have come across any historical rubbish pits eroding out of a bank, you can save a lot of time trying to figure it out for yourself!

Historical Information

The first step to anticipating where archaeological evidence will likely be is understanding the area’s local history. That information may come from published books, photographs, old survey plans, online records or descendants’ lips today.

These layers of information are essential to building a picture of where people did what in a landscape and, therefore, where physical evidence of those activities may be preserved.

For example, I have spent much time perusing historical survey plans and Māori Land Court records when assessing the potential for archaeological evidence in Waikato.

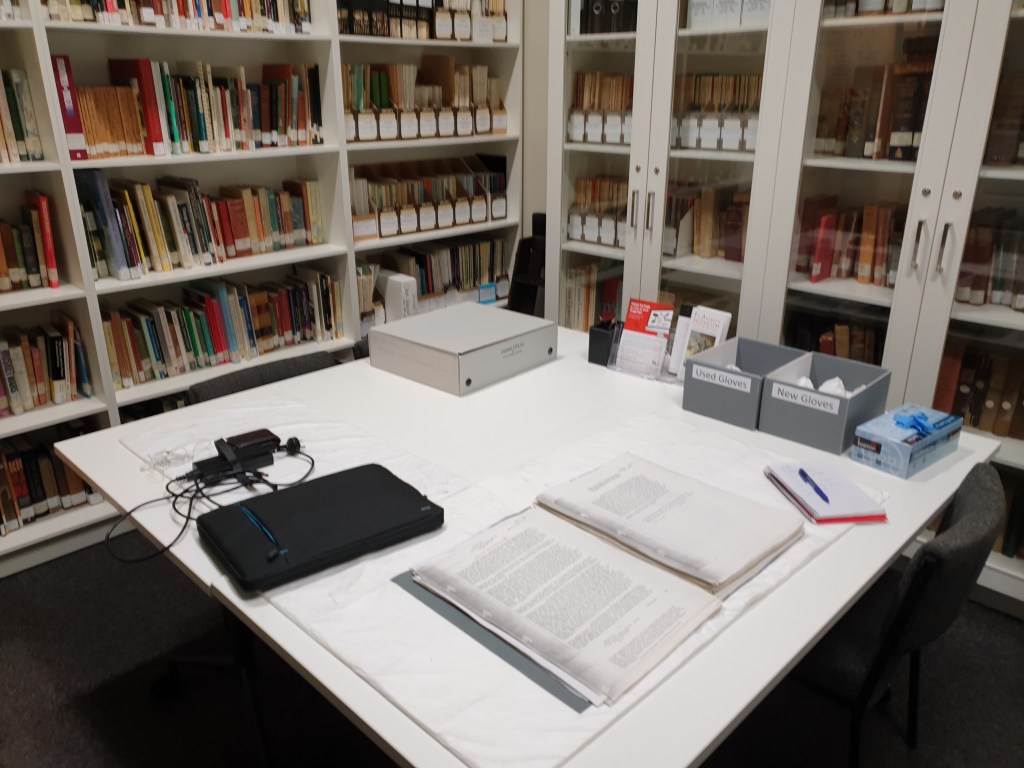

Legacy data: what do we already know?

People, including archaeologists, have gathered information about cultural heritage places for decades. This information can be in the form of recorded archaeological sites on some form of databases like the New Zealand Archaeological Association’s ArchSite, reports and publications, old photographs, drawings or other forms of data.

There is no point in reinventing the wheel whenever you step outside, so building on what others have recorded is best. [insert giant shoulder standing proverb here!]

For example, excavations during the Rua Mātītī Rua Mātātā Research Project on pā tawhito (historical settlements of tangata whenua) in Waikato were often targeted at places that had already been investigated by earlier archaeologists, such as Peter Bellwood’s excavations at Mangakaware.

Aerial & Satellite Imagery

Some archaeological evidence is best seen from above. Images from planes, drones and satellites allow us to see surface features like terraces, building foundations or irrigation trenches that are difficult to see from the ground.

Images taken at different times can show how the landscape was once different from today. These datasets can also aid researchers in viewing hard-to-reach places.

Can you pick out the terraces, agricultural alignments, defensive ditches and paths on Motukorea below?

LiDAR: Shooting Laser Beams at the Ground

No, it’s not a space-age weapon – it’s LiDAR! Archaeologists shoot laser beams at the ground from aeroplanes, drones and sometimes from tripods on the ground to create super-detailed maps of the terrain.

Unfortunately (or maybe fortunately), you cannot see or hear the lasers, so it is perhaps less exciting than the image in your mind. However, the results can be remarkable and really helpful for archaeologists to identify potential archaeological evidence.

LiDAR can help to detect areas where people have changed the ground surface in some way, such as the construction of ditches, banks, walls, terraces, structures, water races or pits. You can check out its effectiveness in this review article by Josephine Hagan and Dr. Andrew Brown.

Here is a quick video explainer on the power of LiDAR in the Amazon, which has helped locate archaeological landscapes beneath dense rainforest canopies.

Field Survey: On the Ground with a Magnifying Glass and a Smile

Surface Evidence

Sometimes, archaeological evidence reveals itself to you directly, but you kind’a have to be there in person to see it.

Archaeologists have a sharp eye for artefacts and features on the surface. Whether it’s a mysterious ceramic fragment or a strangely shaped rock, these clues can help indicate buried evidence nearby.

That’s why surface inspection is one of the most powerful tools for archaeologists to know where to excavate. It is all good and well to use aerial imagery, historical records and fancy lasers, but it is generally helpful to go and inspect the ground surface.

Erosion, fallen trees and slumps can often expose buried archaeological evidence you can only detect by getting out in the field and using your eyes.

Geophysical Techniques

Sometimes, all the above techniques are not enough to identify archaeological evidence. For all you know, you could be walking over layers of century-old human occupation without even knowing it!

A suite of techniques within the geophysics family can detect physical changes beneath the ground that people may have created in the past.

These changes could be making a fire that became buried, digging a trench, burying a person’s body in a grave or constructing wall foundations.

Let’s look at a few of these techniques:

- Changes to the ground by digging or building things, or the burying of magnetic objects like volcanic rock or metal can alter the earth’s local magnetic field in a small way. Magnetometry is a tool that can detect these changes even when you cannot see any evidence of those modifications above ground.

- Different materials resist electrical currents to different extents. Metals and sediments with high water content conduct electrical currents really well, while some rocks and dryer sediments can inhibit those currents. Resistivity arrays detect these subtle changes in the ground’s electrical resistivity.

- Ground penetrating radar is another technique that sends radar waves below the ground to detect hard objects or changes in layers of sediment.

Ground testing

Based on all these techniques, archaeologists might have a hunch of where buried archaeological evidence might be.

This hypothesis can be tested by making small explorations into the ground — always following the local tikanga and legislative requirements.

Techniques range from using a metal spear probe to a spade-width test pit into the ground to detect changes in sediment colour, texture and compaction, and identify evidence of past human activity, such as shell (e.g. from midden), charcoal, burnt rocks, cultivated soils, glass or ceramic fragments.

All of these materials hint at there being further buried archaeological materials nearby.

Predictive Modelling: using maths before you dig

Now, I know what you’re thinking: archaeologists and math? By crunching data from known locations of archaeological evidence, the local environment, and cultural patterns, we can predict where other similar materials may be buried.

Predictive models have been used on a handful of occasions in Aotearoa New Zealand to determine the likelihood of development earthworks modifying or destroying archaeological evidence (e.g., Northland SH11 and Kāpiti Coast).

Usually, predictive modelling tools are less helpful when determining whether archaeological evidence is buried within the 10 meters or so around you. In those situations, the other techniques mentioned above may be more useful.

Even when you are really prepared, archaeology can be full of surprises, such as this late nineteenth-century garden path nestled beneath a concrete parking building in downtown Auckland!

Summary

So there you have it, intrepid explorers of history – the thrilling methods that archaeologists in Aotearoa New Zealand use to track down the whispers of the past. It’s a blend of high-tech wizardry, good old-fashioned research, a little bit of sifting through dirt and a sprinkle of luck.

To figure out where buried archaeological evidence is located (and sometimes decide where to dig), archaeologists use desktop research (including historical information, aerial photographs or LiDAR), field survey to inspect the ground, geophysics, small test investigations and predictive modelling.

In reality, archaeologists use a combination of these techniques depending on the constraints of the kaupapa (project, purpose).

Archaeologists have great power in identifying potential buried archaeological evidence – tapuwae o ngā tūpuna. Excavation is an invaluable tool to learn new things about the past, recover lost knowledge, or salvage evidence before it is destroyed by coastal erosion or a new road.

On the other hand, the excavation is destructive – no matter the detail in which the site was recorded. Therefore, archaeologists have a responsibility to only excavate when absolutely necessary and within the tikanga or culturally safe way of doing things of descendant communities.

Interested in engaging more with archaeology? Check out this post. Otherwise, subscribe to keep up to date with my next posts.

Mauriora, Zac

One thought on “How do archaeologists know where to dig?”